Upcoming Events

PAST EVENTS

CEGU Colloquium

from truth to power: the political framing of climate change in us environmental discourse

Elaine Colligan, PhD Student, Political Theory

Friday, May 16, 2025

12:30–2:00 pm

Room 344

1155 E. 60th St.

Abstract

Environmentalism often functions as a form of public political theorizing, articulating conceptions of power, justice, and politics itself to render environmental problems thinkable. This chapter examines how the U.S. climate movement has historically problematized climate change as a political issue, tracing the evolution of this articulation through the work of two key figures: Al Gore and Bill McKibben. I argue that Gore’s early 1990s framing of climate change as a moral problem reflected a strategic, if ironically depoliticizing, figuration of “the political.” His vision transformed climate change from a scientific hypothesis into a political problem by subordinating politics to human morality, precluding critique of the power relations driving the crisis. Thirty years later, McKibben reconfigured climate change as an agonistic struggle against fossil fuel interests, revindicating politics as a site of contestation and collective agency. Yet, McKibben’s framing also exposes the conceptual exhaustion of inherited categories, blurring distinctions between industry and state and raising new questions about power in a planetary fossil regime. By situating these shifts within their historical “problem-spaces,” this chapter offers a genealogy of how climate change has been rendered political and reflects on the need for new political imaginaries adequate to the current conjuncture.

CEGU Colloquium

Western chemistry meets japanese soil: race, rice, and chemical fertilizer in modernizing japan

Dr. Hiromi Mizuno, Associate Professor of History, University of Minnesota Twin Cities

Thursday, May 8, 2025

3:30–5:0pm

Center for East Asian Studies EATRH Workshop

CEAS 319, 1155 E 60th St.

More Info

Co-sponsored by the East Asia: Transregional Histories Workshop

CEGU Colloquium

Black resonance in the city: Mapping the placemaking practices of the black house music and cultural community of chicago

april l. graham-jackson, Postdoctoral Scholar, Mansueto Institute for Urban Innovation, Chicago Studies, and CEGU

Friday, April 11, 2025

12:30–2:00 pm

Room 344, 1155 E. 60th St.

More Info

In this talk, I will present my research on the placemaking practices of the Black house music and cultural community of Chicago and how they developed an alternative map of Chicagothrough house music, house culture, and what I termed, “house geographies.” Since the Great Migration, Black Chicagoans were confined to the South and West Sides due to the racialization of space and how it shaped the ways they live in and move through their city. Geographers, urban social theorists, and ethnomusicologists examine Black Chicago and its rich music and cultural histories and how it deepens our understanding of Black urban life. Less attention has been paid to the spatial dimensions of Black music, sound, and culture across Chicagoland. I highlight the relationships between place-based music, sound, and geography as a framework for Black “a-where-ness” in Chicago through a Black sense of place and how Black expressive forms counter discriminatory processes to produce spaces that do not harm Black life. I turn to Black acoustemologies—how Black people know, order, and understand their worlds through what is audible to and for them—to demonstrate how the Black house kids repurposed abandoned spaces as sites of resistance, but also for kinship, joy, and pleasure. By journeying through the chord progressions of Black life, I foreground the placemaking practices of the Black house kids who constructed Black spaces in a “house that is only as safe as the flesh [1]” in one of the most racially segregated cities in America.

[1] Katherine McKittrick. Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle. University of Minnesota Press. 2006. #citeBlackwomen

april l. graham-jackson is a Postdoctoral Scholar in the Department of Sociology and a Postdoctoral Research Fellow with the Mansueto Institute For Urban Innovation at the University of Chicago. She is also a Postdoctoral Research Affiliate with Chicago Studies, the Committee on Environment, Geography, and Urbanization (CEGU), and the Urban Theory Lab. A proud third-generation Black Chicagolander, april’s research brings together Black geographies, the political economy of scale, racial capitalism, music, and sound and how these forces shape Blackness and Black life across the Chicago Metropolitan Area or what she termed Black Chicagoland. april holds a PhD in Geography from the University of California, Berkeley. She graduated summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa from Mount Holyoke College as the first person with a bachelor’s degree in Black Geographies. You can find april musing with Roderick, her husband and artistic partner, at BlackChicagoland.com.

CEGU Colloquium

towards a 'rural take-off': agricultural intensification and ecological change, 1979–2000

Rohan Chatterjee, PhD student in History, UChicago

Friday, March 28, 2025

12:30–2:00 pm

Room 344, 1155 E. 60th St.

More Info

This paper is a draft of part of the fifth and final chapter of my dissertation, “When a World Moves On: Land, Life and Struggle in the Peruvian Andes.” In it, I ask us to reconsider the history of peasant agriculture over the twentieth century. Indeed, today peasant agriculture is typically viewed as a marginal activity, an anachronistic holdover from an agrarian past doomed to disappear. And yet by taking Peru as a case study, I demonstrate how amidst historic demographic growth, the countryside filled with a record number of peasants, farming at a level of intensity never seen before. In so doing, I challenge dominant conceptual frameworks for Peruvian and Latin American history by revealing a remarkable expansion of peasant agriculture as the most important driver of change across much of the countryside. In this chapter, I point to how the rapid proliferation of peasant agriculture came as part and parcel of an equally stunning period of expanding human activity and anthropogenic change as well as propose the need to broaden existing accounts of that phenomenon beyond a few regions (the Global North) or certain activities (fossil fuel use, industrialization, plantation agriculture). In brief, my research stresses the need for a much closer examination of peasant agriculture to better understand the world we have inherited.

To tell the story of the dramatic growth of peasant agriculture, my dissertation uses a hundred-year microhistory of a single valley called Antapampa. Beginning at the dawn of the twentieth century, chapter one paints a picture of a peasant agriculture still defined by a relatively low person-to-land ratio as well as an absence of fossil fuels, mechanized technology, or modified seeds, in a basically stable ecological setting. Over the next two chapters, covering the period 1900-1968, I show how historic population growth saw estate and communal land concentrations collapse, all amidst one of Latin America’s largest ever peasant movements. In chapter four, 1968-1980, I detail how with limited arable plots available for redistribution, the continent’s most radical agrarian reform failed to address mounting land pressure. In the final chapter, 1980-1995, I document how extreme land fragmentation, along with technical support from Green Revolution inspired NGOs and technologies, engendered a mass intensification of agricultural production and an unparalleled upheaval of the ecological status quo.

CEGU Colloquium

adam Nocek

Associate Professor, Arizona State University

Friday, February 28, 2025

12:30–2:00 pm

Room 344, 1155 E. 60th St.

More Info

This talk offers a philosophical meditation on various social and ecological interventions made in the relatively new field of urban agroecology. Specifically, it shows how urban agroecologies are situated at the intersection of a complex set of debates in urban design/planning, the agricultural sciences, and social and political activism on how food production in urban centers has political stakes. While some of these stakes will need revising given the technological and social complexity of urbanization in the twenty-first century (it’s a planetary in scale), the talk ultimately attempts to reframe this debate in terms of important philosophical questions urban agroecology raises but is generally unequipped to answer (e.g., on the divisions between biology and technology, the urban and the rural, and even computable and incomputable problems). To make headway, the talk argues that what remains underdeveloped is how agroecological urbanism is a design problem that lacks a theoretical framework. And it’s by articulating the nature and scope of designing in this context, with help from Alfred North Whitehead on social ecologies, that the field can move beyond certain conceptual and practical impasses. The talk ultimately charts a path for philosophical design and urbanism to intervene in the social ecologies of agricultural production across diverse urban landscapes.

CEGU Colloquium

The electric new deal: Roosevelt’s national power policy and the american state’s changing relationship to energy

Margot Lurie, PhD Student, Sociology

Friday, January 31, 2025

12:30–2:00 pm

Room 344, 1155 E. 60th St.

More Info

During the New Deal, the federal government radically reimagined its relationship to energy through the pursuit of a National Power Policy, which included the creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority, the Rural Electrification Administration, and the amendment of the Federal Power Act. At a time when the energy sector was almost entirely privately-controlled, the Roosevelt administration envisioned a greatly expanded role for the federal government in the generation and transmission of electric power. Through an historical sociological study of the development of the New Deal power program, I will explore why increasing the supply and consumption of electricity nationwide became a state priority. I identify an emergent defense-industry-consumption “nexus”, which came to rely on an abundant supply of cheap electricity during the New Deal. Federal efforts to increase generating capacity and create a national “grid” helped funnel electricity toward capitalist industry, in no small part to prevent future war-time power shortages. New supplies of electricity that could not be used immediately by industry were directed toward household consumption, particularly in rural areas. I suggest that, during the New Deal, cheap electricity was firmly established as a general condition of production and reproduction, creating a new role for the American state: maintaining the electric systems and securing the fuel necessary for their continued operation. The paper concludes that theorizing the modern state’s relationship to energy, particularly attending to how state priorities are channeled into actual domestic energy systems, can help shed light on key state functions, with lasting political and environmental consequences.

CEGU Colloquium

theatres of empire: A humanist environmentalism of colonial space

Tyler Lutz, PhD Student, English

Friday, January 24, 2025

12:30–2:00 pm

Room 344, 1155 E. 60th St.

More Info

Colonial maps, geographer Matthew Edney asserts, constitute an unworkably backwards analytic object; cartographic practice was so central to the establishment, operation, and expansion of European empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that it would be more historically and conceptually apt to speak of the empires that maps made rather than its converse. To entertain this conceptual inversion is to foreground how the technologies of cartographic production—panoptic surveys, extraction and assimilation of incommensurable sensory stimuli, lines scored into formerly smooth intaglio printing plates, etc.—were dilated and ramified into technologies of colonial administration tout court. What Edney’s claim leaves unspoken—and what this paper aims to more robustly articulate—are the ways the larger aesthetic machinery of empire can be read off of the visual homunculus supplied by its underlying cartographic imaginaries. Maps, that is, not only mimetically delimit the architectonic parameters of colonial space, but also perform the rhetorical work of translating empire into a site of affective engagement and aesthetic intervention. Drawing on collections held in Britain and across the subcontinent, this paper tracks how imperial maps of British claims in South Asia self-consciously conflate disparate visual-rhetorical modes of blankness in order to transcend and transmute the map’s own epistemic limitations. Colonial maps, I argue, deploy an arsenal of formal tropes—blurry distinctions between proper and generic place names, reduplicated toponyms, and compositional skewing notably among them—to convert ambiguity from an epistemic problem to a primarily aesthetic one. Taking the performativity of the inscrutable, cartographic blank gaze seriously helps us recast British empire as a project that not only obsesses over its own epistemic failure but also, more strongly, recovers this failure as a motive condition of its intemperately expansionist place-making: of its maps’ dizzying ability to not just passively register or index space, but rather rhetorically produce it anew, as if from whole cloth.

CEGU Colloquium

Climate politics talk series: Alyssa Battistoni

Alyssa Battistoni, Assistant Professor of Political Science, Barnard College

Sponsored by the Political Science Department

Friday, December 6, 2024

12:30-1:50 pm

Foster Hall, Room 107

CEGU Colloquium

The Roadblock state: highways, automobility, and taxation in lebanon, 1920-1950

Zachary Davis Cuyler, Assistant Professor of History, University of Illinois-Chicago

Friday, November 15, 2024

12:30-2:00 pm

Room 344, 1155 E. 60th St.

More Info

This chapter focuses on the assembly of the highway network under the French Mandate and the effects that this infrastructure had on the spatial logic of the Lebanese state. It traces the emergence of Lebanon as a “roadblock state” in which state power was strongest at chokepoints along these infrastructural channels—especially points where the new highway network that Mandatory authorities assembled across the 1920s met the new borders imposed upon the post-Ottoman mashriq. This chapter relies on theories of state formation developed in studies of colonial and postcolonial Africa and the Caribbean. By taking a transnational and infrastructural approach to Lebanese state-formation, and by borrowing from studies of Africa and the Caribbean to do so, I aim to counter exceptionalizing tendencies within academic, policy, and popular discourse on Lebanon that attribute its distinctive historical trajectory to internal rather than relational processes. Moreover, centering the state in this way will further recent interventions by historians of Lebanon like Ziad Abu-Rish, Hicham Saffieddine, and Hannes Baumann, who have countered exceptionalizing narratives concerning the formation—or purported absence of the Lebanese state.

CEGU Classic Texts

Anthropology and the Banana Wars: Trouillot’s Dominica

Ryan Cecil Jobson, Neubauer Family Assistant Professor of Anthropology, University of Chicago

Friday, November 1, 2024

12:30-2:00 pm

Room 344, 1155 E. 60th St.

More Info

A CEGU Classics Lecture on Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s Peasants and Capital: Dominica in the World Economy (1988).

Drawing on the model of the University of Pennsylvania’s “Africana Classics” lectures, we hope to launch the Classic Texts Lecture as an annual opportunity for faculty to present on key works in their intellectual development, in the hopes of expanding the notion of a theoretical canon for CEGU. We encourage all students in our Colloquium community to attend, particularly those in the CEGU Graduate Certificate, in order to engage in lively discussion about the core questions and geographies that motivate our collective work and struggles.

CEGU Colloquium

on ruralization in brazilian politics: From post-abolition to bigag

Christopher Lesser, Assistant Professor, Global Studies, UNC-Charlotte

Friday, October 11, 2024

12:30-2:00 pm

Room 344, 1155 E. 60th St.

More Info

The last and largest slave society in the Americas, Brazil is now the world’s largest agricultural economy and its most unequal, with inequalities organized along clearly racialized lines. This talk, entitled “On Ruralization in Brazilian Politics,” explores how rural spaces became central to new forms of economic exploitation and social domination after the abolition of slavery. Although often imagined as an evanescent intermediary step between the primitive and the modern, the rural has continued to grow and has proliferated in Brazilian political economic and social life. In 1993, the geographer Milton Santos wrote that “modern Brazil is a nation in which the agricultural population is growing faster than the rural population.” Yet today, an increasing number of the representatives in Brazil’s legislature describe themselves as “ruralistas” or ruralists. And paradoxically, it is ruralism which most perfectly embodies the oligopolist techno-scientific agrarian economy which Santos associated with an increasingly divided and unequal society. If the rural and the urban have apparently traded places then, the racial connotations of the rural have also been symbolically inverted, due in part to a politics of rural dispossession that foreclosed Black access to landed property and environmental resources in the long-century after abolition. “On Ruralization” explores how dispossession has taken place not just through the enclosure of land and commodification of land-based resources, but also via the appropriation of environmental work in its productive and reproductive capacities. The talk details how knowledge developed by agronomists, geographers, and ecologists working in fields from bovine genetics to conservation ecology legitimated scientific authority over new types of social labor and value at the scale not of the individual subject or even the species, but rather at the level of the environment or ecology.

EVENTS: 2023–24

CEGU Colloquium

Alyssa Mendez, Ph.D. Student in Anthropology

Friday, May 17, 2024

12:30pm

Room 344, 1155 E. 60th St.

CEGU Colloquium

Brett Christophers, Uppsala University

with interlocutor Jo Guldi, Emory University

Friday, May 3, 2024

12:30pm

Room 344, 1155 E. 60th St.

More Info

What if our understanding of capitalism and climate is back to front? What if the problem is not that transitioning to renewables is too expensive, but that saving the planet is not sufficiently profitable? This is my claim. The global economy is moving too slowly toward sustainability because the return on green investment is too low. Today's consensus is that the key to curbing climate change is to produce green electricity and electrify everything possible. The main economic barrier in that project has seemingly been removed. But while prices of solar and wind power have tumbled, the golden era of renewables has yet to materialize. The problem is that investment is driven by profit, not price, and operating solar and wind farms remains a marginal business, dependent everywhere on the state's financial support. We cannot expect markets and the private sector to solve the climate crisis while the profits that are their lifeblood remain unappetizing. But there is an alternative to providing surrogate green profits through subsidies: to take energy out of the private sector's hands. An essential intervention, The Price Is Wrong is as politically far-reaching as it is factually illuminating.

Presented in affiliation with the Economic Planning and Democratic Politics project at the Neubauer Collegium

CEGU Colloquium

Mehrnoush Soroush, CEGU & NELC

with respondant Mary Beth Pudup, CEGU

Friday, April 12, 2024

12:30pm

Mansueto Lounge, 1155 E. 60th St.

CEGU Colloquium

Emma Pask, Ph.D. Candidate in Anthropology and the Conceptual and Historical Studies of Science

with respondant Hadeel Badarni, Ph.D. Candidate in Anthropology

Friday, April 19, 2024

12:30pm

Mansueto Lounge, 1155 E. 60th St.

More Info

A dilapidated cotton warehouse owned by Huntsville Prison in East Texas became the home to over a million bats in the 1990s. This state-protected urban bat colony now poses a public health threat to both the residents of the town and the men imprisoned across the street. Human life and wildlife are treated as worlds apart even in their shared ecological reality: as unlivable heat worsens every summer, the inmates are denied air-conditioning and animal migratory patterns are drastically altered, but only the bats are advocated for by the state of Texas.

My dissertation is a historically oriented anthropological investigation of Texas’ ecology and the ecologists who study it. It is particularly interested in the settler colonial formation of “the range” as an ecological, geographic, mythical, and political landscape. I propose to present material from the third chapter of the dissertation to CEGU’s workshop, which explores the study and management of human-wildlife conflicts in Texas—what I call their arrangements. My ethnography of the state-employed ecologists called in to resolve the conflict at the Huntsville prison serves as this chapter’s central example. By exploring the way scientists navigate the boundaries of humans and animals, species and race, prisoners and pests, and protection and threat in this complicated terrain and within this case study, I ask how health – of animals, Texans, and the state as a whole – is configured and re-configured on the range and under the conditions of runaway climate change.

CEGU Colloquium

Venus Bivar, Associate Professor of Environmental History, University of Oxford

Friday, March 29, 2024

12:30pm

Mansueto Lounge, 1155 E. 60th St.

More Info

My current book project, Unsafe Harbour: A Political Ecology of Postwar Marseille, is rooted in the intersecting histories of industrial pollution, economic development, and urban planning. Pulling together these various research threads is a lawsuit concerning ricin poisoning at Le Corbusier's Cité Radieuse. As an iconic embodiment of all that was promised by modernity, the building serves as a starting point for thinking about the various postwar projects that attempted to forestall economic decline, from the expansion of port facilities on the periphery to gentrification efforts in the centre. By examining the environmental fallout of these projects, this research contributes to our understanding of how the logic of extractivism has shaped the fortunes of the city and its people.

Venus Bivar was recently appointed to the University of Oxford's first dedicated post in environmental history. Her research interests lie at the intersection of economic history and the environment, and in particular she is interested in the extraction of natural resources, industrial pollution, and economic growth. She is currently writing a book on the environmental consequences of the rise of petrochemicals in postwar Marseille. Her first book, Organic Resistance: The Struggle Over Industrial Farming in Postwar France (UNC Press 2018), was awarded the J. Russell Major Prize from the American Historical Association, as well as an honourable mention for the Society for French Historical Studies' Pinkney Prize, and was shortlisted for both the Canadian Historical Association's Wallace K. Ferguson Prize, and the Council for European Studies' Book Award.

CEGU Colloquium

Derick Anderson, Instructional Assistant in CEGU

Friday, February 23, 2024

12:30pm

Tea Room, 1126 E. 59th St.

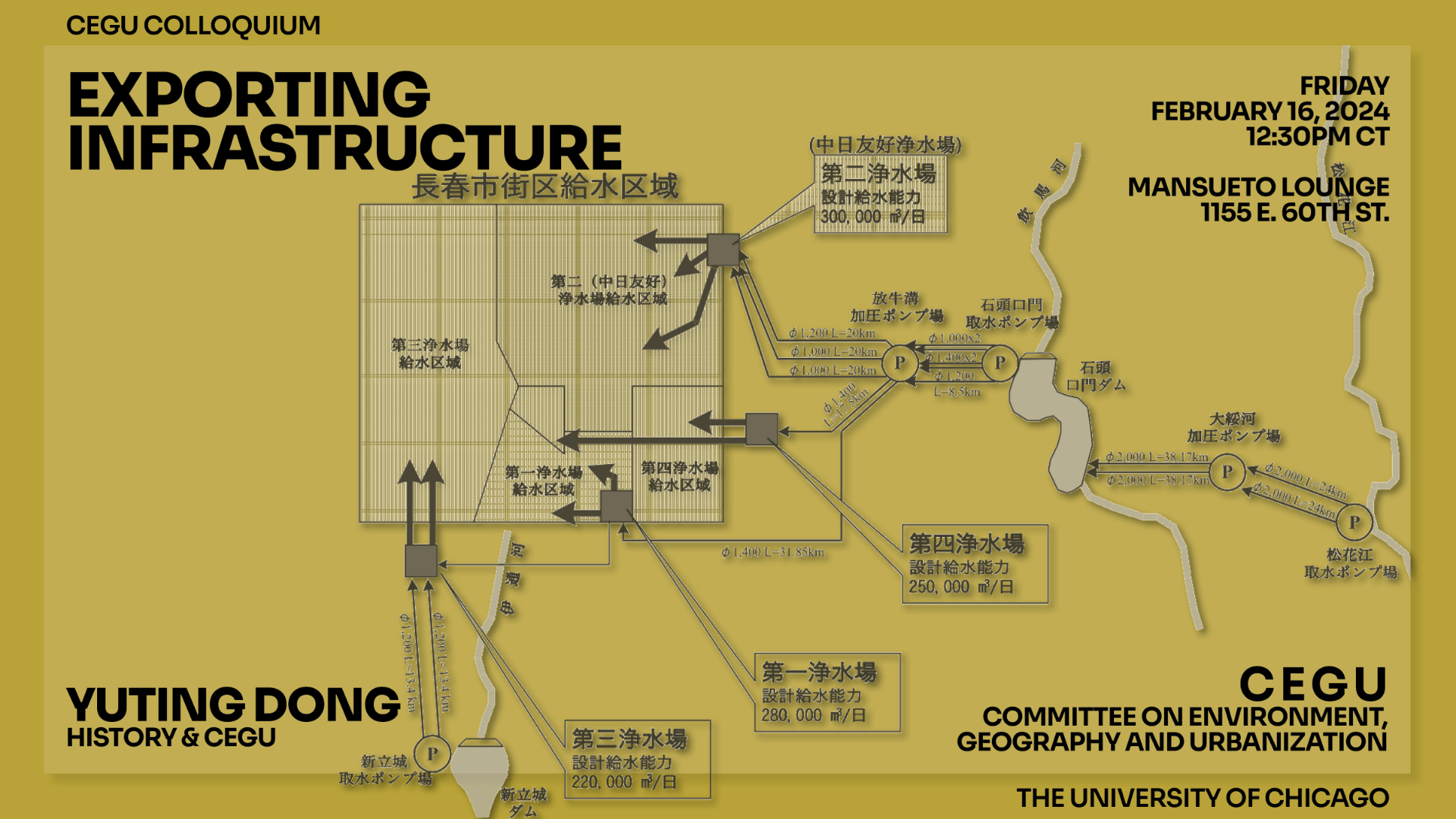

CEGU Colloquium

Yuting Dong, History & CEGU

Friday, February 16, 2024

12:30pm CT

Mansueto Lounge, 1155 E. 60th St.

More Info

From 1986 to 2002, Japan has offered three rounds of financial and technological assistances in building and expanding Changchun’s second Water Purification Plant (WPP). With Japan’s assistances, this regional capital in Northeast China is equipped with a world-class water filtration system that provides crystal clear and clean drinking water to its residents. As the last chapter of my book manuscript (Japan’s Infrastructure Empire), this paper explores the history behind such assistances and show how imperial infrastructure building casts a long shadow in the former colonies as the imperial infrastructure established water standards and internalized a form of understanding of infrastructure. Moreover, this chapter concludes the book by pointing out issues associated with this infrastructure-centered approach in addressing social, political, and ecological problems. The positive consideration of infrastructure as a solution in both Japan further twists the view of the imperial past and provides an insufficient method in the face of current climate crisis.

Yuting Dong is an assistant professor in the Department of History and CEGU. Her research focuses on Japan’s empire, infrastructure studies, history of labor and of expertise. Before joining Chicago’s history department in 2021, she received her doctoral degree from Harvard University. Her work is published in Modern Asian Studies, Technology and Culture, and International Journal of Asian Studies.

CEGU Colloquium

Pauline Goul, Romance Languages & Literatures + CEGU

Friday, February 9, 2024

12:30pm CT

Mansueto Lounge, 1155 E. 60th St.

More Info

This chapter provides a new reading of the intricate relationship between Montaigne’s two essays on the New World, “Of Cannibals” and “Of Coaches”, arguing that their affective grounding allowed Montaigne to formulate an anti-colonial, ecological critique of the conquest. From an attention to environmental change in “Of Cannibals” that reveals a critique of expansionism centered on one plagiarized anecdote, to a carefully constructed lexicon of sustainability throughout both essays that reflects on the risks of overloading nature and on limits, I argue that, ultimately, both essays denounce colonization as a movement of subjugation and violence. Montaigne exposes how, by confusing human beings and nonhuman environment as resources, Europeans have rendered themselves insensitive to their responsibility in processes of devastation that have only grown larger to this day.

CEGU Colloquium

Chaos in the Heavens: The Forgotton History of Climate Change, 15th–20th Centuries

Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), Paris

Friday, January 26, 2024

12:30pm CT

Mansueto Lounge, 1155 E. 60th St.

More Info

Nothing could seem more contemporary than climate change. Yet, in Chaos in the Heavens (Verso, 2024), Jean-Baptiste Fressoz and Fabien Locher show that we have been thinking about and debating the consequences of our actions upon the environment for centuries. The subject was raised wherever history accelerated: by the Conquistadors in the New World, by the French revolutionaries of 1789, by the scientists and politicians of the nineteenth century, by the European imperialists in Asian and Africa until the Second World War. Climate change was at the heart of fundamental debates about colonization, God, the state, nature, and capitalism. From these intellectual and political battles emerged key concepts of contemporary environmental science and policy. For a brief interlude, science and industry instilled in us the reassuring illusion of an impassive climate. But, in the age of global warming, we must, once again, confront the chaos in the heavens.

Jean-Baptiste Fressoz is a historian at the CNRS in Paris. He is the author of Happy Apocalypse. A history of technological risk; The Shock of the Anthropocene (with C. Bonneuil); Chaos in the heavens (with Fabien Locher) and Sans transition. Une nouvelle histoire de l’énergie.

CEGU Event, CEGU Colloquium

The WAstemen's fossil flora: geology and labor in britain's energy transition , 1819-1845

Fredrik Albritton Jonsson, History & CEGU

Benjamin Morgan, English & CEGU (discussant)

Friday, November 17, 2023

12:00–2:00pm CT

SSRB Tea Room, 1126 E. 59th St.

More Info

The deep coal mine was the work site of Carboniferous geology. The richest evidence came not from the coal seams themselves but the shale layers that surrounded them. This meant that fossils came to light principally when tunnels collapsed. Fossil collection in the colliery was a high-risk activity associated with maintenance, repair, and danger to life and limb. The key figure in such work was the wasteman. The task of the wasteman was to walk the pits to survey the air courses and keep them in good repair. The wastemen also took stock of the stability of pillars and old workings. Sigillaria fossils posed a particular risk to colliers. Their heavy trunks frequently slipped out of the roof, leaving gaping holes, sometimes as wide as five feet in diameter. Constant surveillance of waste and shale was thus a critical task, vital to the security of the colliery and the lives of the people there. Yet references to the work of the wasteman are very rare in geological texts from the period. In natural theology, the divine work of the Creator took precedence and erased the social world of the collier. Fossils were seen as emblems of providential time, not products of the wasteman’s working day. Sigillaria and other coal plants had purged the atmosphere of surplus carbonic acid and deposited it in the Carboniferous strata. Thanks to the accumulation of carbon in the underground, the atmosphere of the planet had become “fit for the support of animal life, and human habitation.” Coal was not just the fuel of British wealth but also the life-giving force that had made the planet habitable. The erasure of the colliery worker from geology paved the way for a cosmology of carbon. At the same time as mining engineers and wastemen traced the gas flows inside the coalmine, geologists began to imagine God as the wasteman of the carbon cycle, regulating the atmosphere, channeling carbon back and forth through plants, earth, and air.

CEGU Colloquium, Student Event

Friday, November 10, 2023

2:00–3:00pm CT

Room 344, 1155 E. 60th St.

More Info

All those currently seeking to earn a CEGU Doctoral Certificate are obliged to attend. Anyone interested in the CEGU Doctoral Certificate are welcome. Attendance in person is preferred, but if you are unable to attend in person, the meeting will be also available via Zoom. You will receive a link upon submitting the registration form.

CEGU Colloquium

Julia Mead, Ph.D. Candidate in History

Wednesday, November 1, 2023

4:00–5:30pm CT

John Hope Franklin Room (224), Social Science Research Building (1126 E. 59th St.)

More Info

The post-socialist period in East Central Europe was a period of rapid energy transition. From 1948-1989, states in this region relied almost exclusively on domestic coal for industrial and residential heating and electricity, in the process transforming their mining regions into some of the most toxic environments in the world. After 1989, as newly elected governments and foreign economic advisers privatized state industries through a process of “shock therapy,” wealthy investors bought majority shares in coal mining enterprises and shuttered many mines deemed unprofitable. Using records from the corporate archives of the successor company to the state’s largest coal enterprise, this paper traces the privatization process in Czechoslovakia/Czech Republic as an emblematic case study in social consequences of de-carbonization for energy workers. Under socialism, the state coal mining enterprise was sprawling; hundreds of houses, tens of thousands of apartments, dozens of cafeterias, clinics and hospitals, laundries, recreation centers, hotels, bus depots, dormitories, a travel agency, and even a seaside campground in Bulgaria, all available for free or at extremely low cost to energy workers and their families. The mine’s post-1989 owners concluded that these services must be “converted to a profit-making basis” and, in the process, transformed from rights to commodities.

This paper argues that the privatization process forced government officials, foreign economic advisers, and miners to resolve deep ontological questions: What is a coal mine? Who is a coal miner? Each group had a different answer arising from their divergent assumptions of what elements of the economy and human behavior are “natural.” Miners rejected the idea that economic competition is a natural human (and, indeed, manly) endeavor, arguing instead that “every man naturally seeks certainty in all spheres of life.” This paper treats the process of de-carbonization in post-socialist Czechoslovakia as an ambiguous transition. Cleaner energy and a healthier environment came yoked to new and profound uncertainty for energy workers, in which services workers had long taken as their right—housing, light, heat, leisure, medical care—became governed by the market. In the process, unemployment, homelessness, and poverty, once unimaginable to energy workers, became common.

Julia Mead is an environmental historian of Eastern Europe. She is a PhD candidate in history at the University of Chicago. Her dissertation, “Socialist Rust Belt: Energy, Masculinity, and the End of Czechoslovak Socialism” traces the rise and fall of the Czechoslovak coal industry from 1948-2004 and its relationship to changing norms of masculinity.

CEGU Event, CEGU Colloquium

Megan Black, MIT

Elizabeth Chatterjee, University of Chicago (discussant)

Friday, October 27, 2023

12:00–1:30pm CT

Room 142, 1155 E. 60th St.

More Info

The talk will examine how Friends of the Earth helped make Crested Butte, Colorado's fight against the multinational mining firm AMAX a household name in the 1970s (while neglecting to provide the same level of dug-in support to other communities that, unlike this town, were not inhabited by a nature-seeking group of white elites), asking about the possibilities and limitations of multiscalar activism seeking to move from local to global.

This event is co-sponsored by International House. Please note, this event will take place in person only. A recording will be made available shortly afterwards.

CEGU Colloquium

Elaine Colligan, Ph.D. Student in Political Science

Friday, October 20, 2023

12:00–2:00pm CT

Room 142, 1155 E. 60th St.

More Info

In a moment of world-destroying environmental breakdown, political actors are increasingly claiming that nature should have rights. What are the political stakes of these claims? Against their scholarly critics, who contend that extending rights to nature is a philosophically incoherent idea and thus politically ineffective, I contend that when political actors claim that nature should have rights, they are not attempting to extend rights to a new class of subjects but potentially transforming the concept of rights. This is not to say that nature simply can have rights; I agree that nature’s rights encounter “conceptual strain," both hold that this does not entail that nature’s rights could never “make sense.” If we understand nature’s rights not as a pre-linguistic and pre-political concept, but rather as an everyday practice of making political claims, we can see how these performative acts of democratic persuasion might make sense anew. Innovating at the fuzzy boundary between the rule-bound and radically open character of language, claims that nature should have rights defamiliarize the grammar of both rights and nature.

Co-sponsored Event, CEGU Colloquium

Sarah Newman, Claudia Brittenham, Pauline Goul, and Mariana Petry Cabral

Wednesday, October 11, 2023

5:00pm CT

Assembly Hall, International House (1414 E. 59th St.)

More Info

Garbage is often assumed to be an inevitable part and problem of human existence. But when did people actually come to think of things as “trash”—as becoming worthless over time or through use, as having an end?

Unmaking Waste tackles these questions through a long-term, cross-cultural approach. Drawing on archaeological finds, historical documents, and ethnographic observations to examine Europe, the United States, and Central America from prehistory to the present, Sarah Newman traces how different ideas about waste took shape in different times and places. Newman examines what people consider to be “waste” and how they interact with it, as well as what happens when different perceptions of trash come into conflict. Conceptions of waste have shaped forms of reuse and renewal in ancient Mesoamerica, early modern ideas of civility and forced religious conversion in New Spain, and even the modern discipline of archaeology. Newman argues that centuries of assumptions imposed on other places, times, and peoples need to be rethought. This book is not only a broad reconsideration of waste; it is also a call for new forms of archaeology that do not take garbage for granted. Unmaking Waste reveals that waste is not—and never has been—an obvious or universal concept.

Please join CEGU, the Center for International Social Science Research (CISSR), and the Center for Latin American Studies (CLAS) for a roundtable discussion and reception with the author at International House.

CEGU Colloquium

Yiyun Peng, Postdoctoral Fellow in History

Thursday, September 28, 2023

4:00pm CT

John Hope Franklin Room, SSRB

(Room 224, 1126 E. 59th St.)

More Info

How did uplands, often presumed inhospitable to agriculture, set limits to and provide opportunities for the cultivation of crops? How did mountain people address the difficulties and utilize and shape the upland environment when cultivating hill- and mountainsides? This article goes beyond two lines of well-established scholarship on upland cultivation in general: one that focuses on typically mountain businesses including lumbering, mining, and hunting; the other on environmental degradation as the result of agricultural cultivation. Instead, by focusing on aspects such as infertility, limited water supply, cold temperature, and elevation in late imperial upland Southeast China, this article discusses the ways in which the agricultural cultivators made efforts to deal with the unforgiving environment. It also reveals how the cultivators utilized various seemingly adverse elements in the uplands, such as cliffs and shadowed space, to their advantage.

By the sixteenth century, most of the fertile bottomland in the valleys and basins and some of the easily accessible hillsides in upland Southeast China had been cultivated into paddy fields. Thereafter, against the context of rapid population growth, a large number of people sojourned in this region and went to great lengths to cultivate deep mountains with food and cash crops, including indigo, tobacco, and New World food crops. Through a close examination of the materiality of mountains and the technicality of mountain people’s cultivation activities, this article contributes to a better understanding of making a living in this complex environment through agriculture.

Yiyun Peng received her PhD in history from Cornell University in August 2023 and joined the Department of History at UChicago after graduation as a postdoctoral fellow. She is mainly interested in environmental history, the history of technology, and economic history. While her main focus is on China, she has also been doing research on Southeast Asia, in particular the Malay world. Her dissertation works on a few cash crops and the handicraft industries processing them into commodities—indigo dye, bamboo paper, tobacco, and ramie (a fiber plant) cloth—led to a herbaceous revolution in upland Southeast China from the sixteenth to the mid-twentieth century, which profoundly transformed the region’s environment and society. The dissertation is a winner of the Messenger Chalmers Prize for the best dissertation in the Department of History at Cornell University.

EVENTS: 2022–23

Environmental Studies Workshop

Carboniferous Imaginaries in the South: Colonial Surveying and the Fate of Fossil Energy

Friday, April 14, 2023

12:00pm CT

Room 103, Wieboldt Hall

1050 E. 59th St.

More Info

Geoscientists now routinely examine the movement of continental blocks over deep time to glean information about the possible location of valuable resources. This practice was initially developed and perfected in the nineteenth century through engagements with fossil deposits – coal, gas, and petroleum reserves – and scaled up to global proportions by surveyors working in the southern hemisphere. In this period geologists identified conformities that link fossil fuels in the Paraná basin in Brazil to the Bowen basin of Queensland, through the Karoo basin of South Africa and the original Gondwana coal measures of India. Defined by the distinguishable Glossopteris fossil leaf, southern coal deposits are an energy network in deep time, latterly reinvented as a resource for imperialism, colonialism, and modernization from the nineteenth century.

This paper examines how these resources were conceived during this initial moment of reinvention and begins to map the uses to which they were put. Starting in the late nineteenth century, when colonial geological surveys first began to quantify the extent and value of these southern hemisphere coal basins, the paper explores the interests that surveyors and geologists pursued in the strata and the cultures of exploitation and extraction that developed in the wake of their study. Geologists in India, Australia, Southern Africa, and South America all worked intimately with related carboniferous stratigraphies. By the early twentieth century geologists had concluded, in the terms of Lewis Leigh Fermor (1880-1954), that the key difference between south and north was the considerable fossil energy wealth that the former presented to the latter. These geologists and their patrons in government and business therefore framed the remnants of the supercontinent of Gondwanaland as a vast energy source for various imperial projects.

During the late nineteenth century the resources of the former supercontinent energized imaginations but in the twentieth century they began to support economies. At least in its Permian permutations, ‘Gondwanaland’ came to be associated with coal, and therefore to modernity, wealth production, energy transitions, and to a modern geological south. According to a recent BP report, southern hemisphere deposits still make up about 24.4% of known reserves of high-grade anthracite. In India the Gondwana coalfields make up about 98% of remaining coal reserves. These deposits have been highly significant to industrial and economic development across the global south. By elaborating on this modern history, this paper challenges a (north) Atlantic-oriented history of fossil-fueled industrialization. An antipodean focus on Gondwanaland helps us consider the place of southern sources of fossil energy in nineteenth and twentieth-century growth trends. This offers up the possibility of a new history of fossil energy, coal, and global capitalism rooted firmly in southern geographies, temporalities, and political economies.

Jarrod Hore is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of New South Wales, Sydney and Co-Director of the New Earth Histories Research Group. He is a historian of environments, geologies, and photographies and the author of Visions of Nature: How Landscape Photography Shaped Settler Colonialism (University of California Press, 2022). His current project investigates the underpinnings of modern earth science in a series of geological surveys in late nineteenth century India, Australia, South Africa, Brazil, and Argentina.

Environmental Studies Workshop

Did the Earth Move for You? Human Geological Agency and the Koyna Earthquake of 1967

Sachaet Pandey, University of Chicago

Elizabeth Chatterjee, University of Chicago

Friday, December 2, 2022

12:00pm CT

SSRB Tea Room (1126 E. 59th St.)

More Info

Environmental Studies Workshop

Bathsheba Demuth, Brown University

Matthew Johnson, Harvard University

Owain Lawson, University of Toronto

Jen Rose Smith, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Alexander Arroyo, University of Chicago (moderator)

Elizabeth Chatterjee, University of Chicago (moderator)

Friday, November 18, 2022

12:00pm CT

Harper 104 (1116 E. 59th St.)

More Info

The historical geographies of extractivism and empire cut across the division between “Global North” and “Global South.” This roundtable brings together scholars working on the Russian and North American Arctic, Brazil, and Lebanon for a conversation across regions rarely placed in the same frame. We will trace the surprising parallels and uncanny connections between histories of energy extraction and ecological transformation on very different colonial and capitalist resource frontiers. We will explore, too, sources of hope: the nodes of resistance and alternative imaginaries generated by projects of Indigenous and decolonial worldmaking.

This session of the Environmental Studies Workshop is co-sponsored by the Urban Theory Lab and the Neubauer Collegium Project on Fossil Capitalism on the Global South.

Environmental Studies Workshop

Green Places, Green Aesthetics: (Re)producing Vulnerability and the Spatial Politics of Street Tree Planning in Chicago

Nina Olney, University of Chicago

Friday, November 4, 2022

12:00pm CT

SSRB Tea Room (1126 E. 59th St.)

More Info

The recently-announced Our Roots Chicago plan from Mayor Lori Lightfoot in Chicago, intended to plant an additional 75 thousand trees in ‘vulnerable’ neighborhoods, was met with surprise controversy when several community organizations protested what they deemed to be the potential for environmental gentrification. Troubling the notion of trees as ‘ahistorical’ or ‘apolitical,’ this paper examines how Chicago residents, in pointing to the ways in which the planting of new trees may not be truly sustainable for their communities, reveal deeper connections between the processes of sustainable development and regimes of racial hierarchy in America’s cities. Expanding on Brandi Summers’ work on “Black aesthetic emplacement,” this paper examines how debates around sustainability become the place of contestation over the modern city, wherein urban policymakers turn to a ‘green aesthetic,’ concealing larger histories of environmental injustice, attaching symbols of sustainability to spatialized forms, and greening the image of the neighborhood—making it more appealing to private investment—rather than greening the neighborhood itself.

Nina Olney is an Instructional Assistant in the Committee on Environment, Geography and Urbanization (CEGU) and a recent graduate of the MAPSS program concentrating in Anthropology. Her research examines green gentrification in Chicago, specifically analyzing the role of street tree planning in transforming neighborhoods in terms of aesthetics, vulnerability, and access. Drawing on theories of racial capitalism, political ecology, and critical geography, her work centers the unseen elements of urban environments to trace a larger history of nature as property.